Should Writers Be Allowed to Use AI at All? Rethinking Authorship, Tools, and Ethics

Should writers use AI at all? A reflective look at authorship, ethics, and whether AI is just a modern version of a of dictionary or thesaurus.

There is a growing discomfort in the writing world that few people are willing to articulate openly: should writers use AI at all? The question is loaded because it challenges long-held ideas about what writing is, what authorship means, and how much external assistance is acceptable in the creative process.

What complicates the discussion further is the reality that many writers already use AI in some form, even if quietly. They lean on it to brainstorm, reshape structure, summarise dense research, or produce material that would otherwise absorb hours of unpaid labour. Yet they often feel uneasy acknowledging it, because AI support is still treated differently from other tools writers have used without controversy.

Yesterday, someone said something to me that captures the heart of this tension:

“Writers already use dictionaries, thesauruses, grammar software, and reference books. Isn’t AI simply the modern version of those tools — only faster and more flexible?”

It is a compelling point. Tools have always shaped writing. Writers have never produced work in isolation. But the difference, and the reason this debate matters, lies in what a tool does. A dictionary provides definitions. A thesaurus provides alternatives. AI, by contrast, can generate entire passages, organise arguments, and imitate tone. When a tool begins to produce meaning rather than support it, the ethical boundaries become less clear.

The fear: that AI undermines the meaning of authorship

Much of the concern around AI is rooted in a sense that authorship might lose its coherence. If a tool contributes substantial language or structure, does the resulting work still originate in the writer’s mind?

The Society of Authors raised this issue in a 2023 report on emerging technologies. Several participants worried that books created with significant AI assistance would obscure where the human contribution ended and the machine’s began. One writer summarised the dilemma plainly:

“If a tool shapes the meaning, are we still calling this authorship?”

A 2025 study from the University of Cambridge and the Minderoo Centre echoed this anxiety. More than half of surveyed novelists believed AI would eventually replace parts of their work. Many expressed deeper concerns that their writing had already been used to train commercial models without consent. The report described this as “an identity challenge” for authors: not a fear of competition, but a fear of losing the defining elements of their craft.

AI as a modern tool — and where that argument holds

The argument that AI is simply another tool, like a dictionary or thesaurus, is not without merit. Writers have always sought external guidance. The difference today is the scale of support and the speed with which it arrives.

Studies from the University of Edinburgh and the Alan Turing Institute in 2024 demonstrated that AI, when used to organise ideas or reduce administrative strain, can act as “cognitive scaffolding” that helps writers focus on the interpretive parts of their work. It supports clarity, reduces overwhelm, and creates space for deeper thinking. In these moments, AI behaves less like a ghostwriter and more like a highly advanced reference tool.

Writers facing barriers such as dyslexia, ADHD, chronic illness, or heavy workloads may also find AI an important levelling tool. In this context, refusing AI does not preserve purity; it restricts access. As Kit de Waal often argues in conversations about inclusive writing practices, “Tools aren’t the enemy. Gatekeeping is.”

When AI supports clarity, confidence, or accessibility, it strengthens the writing. When it replaces curiosity, interpretation, or emotional labour, it weakens it.

Where AI crosses the ethical line

The ethical threshold becomes clearer when we focus on the distinct roles that only a human writer can perform. Only the writer can generate intention, emotional resonance, meaning, and interpretation. Only the writer can decide why an idea matters.

A 2024 arXiv paper examining co-authorship with AI found that readers could often sense when meaning had been outsourced. Even when the prose was elegant, it felt “unrooted” because the framing decisions — the genuine thinking — had not come from a human perspective.

This is why the comparison with dictionaries and thesauruses ultimately has limits. A dictionary does not propose your ideas. A thesaurus does not mimic your voice. AI can do both.

For this reason, the ethical test is not “Did I use a tool?” but:

“Am I still the origin of the meaning?”

If the writer remains the source of interpretation, argument, and emotional intention, then AI is simply assisting. If AI becomes the source of those elements, authorship shifts — whether acknowledged or not.

Should writers disclose their AI use?

This is where the discomfort intensifies. Some writers believe transparency is essential; others argue that writing processes have never required disclosure. A 2024 survey by the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society found no consensus. Most authors agreed that the answer depends not on the presence of AI, but on the degree to which it shaped meaning.

A useful rule emerges from this:

If you would feel uneasy describing how much the tool contributed, you already know the answer.

The future of writing depends on intention

The question is not whether writers should be allowed to use AI. Writers have always used tools. AI is simply a more complex and powerful one. The real question is whether writers can use AI without surrendering the qualities that define their work: curiosity, intention, emotional truth, and interpretive depth.

AI can serve those aims if used with clarity and restraint. It becomes dangerous only when used to replace thinking rather than support it.

Dictionaries give you words. Thesauruses give you options. AI gives you possibilities — and with those possibilities comes responsibility.

Writers should not be banned from AI. But nor should AI become an invisible co-author. The answer lies, as always, in intention. The tool does not decide what kind of writer you become. You do.

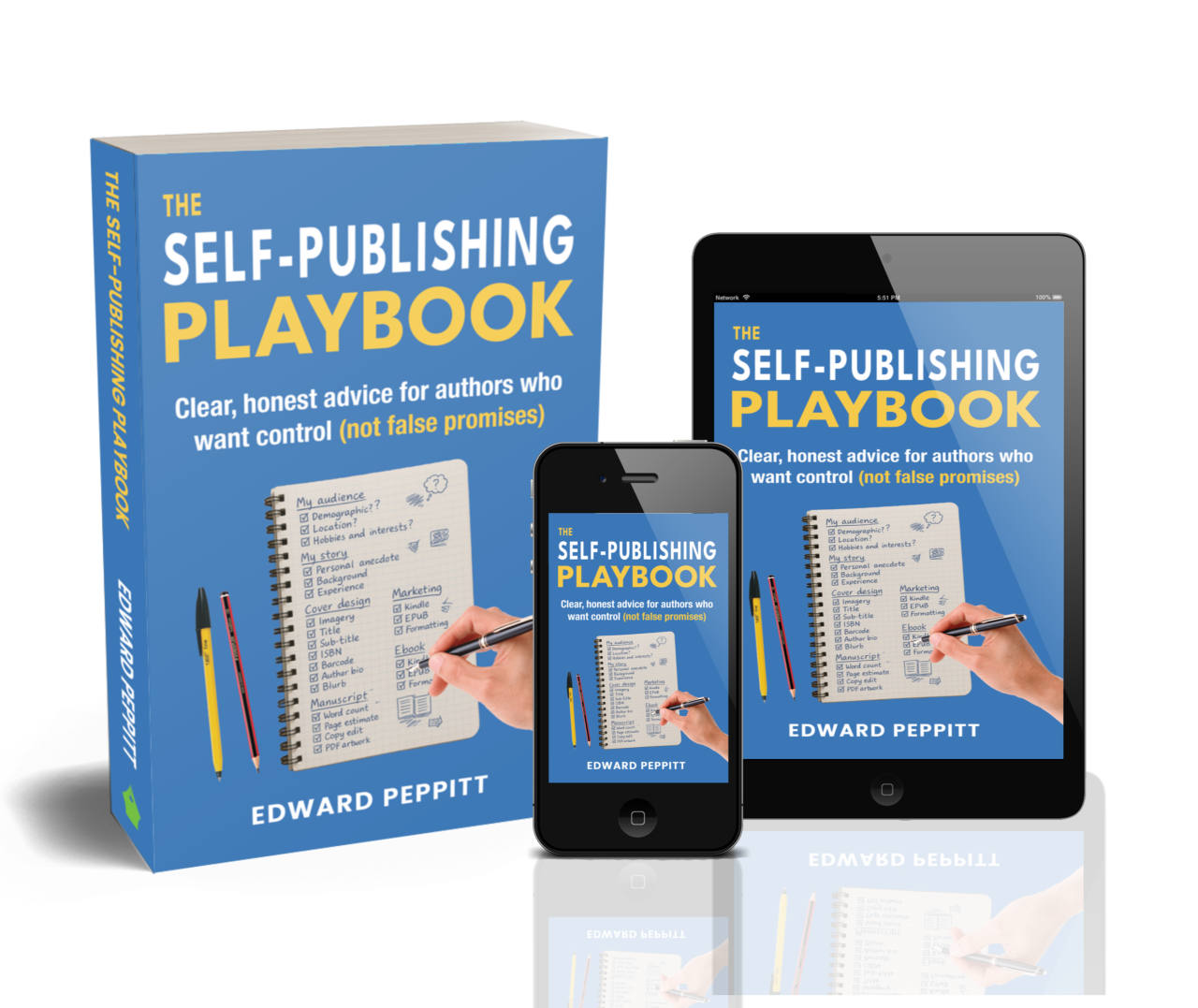

The Truth About AI and Your Writing — Workshop Page

If you’d like a clear, practical introduction to using AI responsibly in your writing, join my live three-hour workshop on Thursday 15th January for just £47 + VAT.

https://www.getpublished.tv/co...

Self-Publish Properly - Live - Workshop Page

For writers preparing to self-publish, check out my 5-day complete guide to writing, editing, and launching your book.

https://www.getpublished.tv/co...

More From the Blog

For more articles for writers who want clarity, confidence, and practical guidance, visit my blog.

https://www.getpublished.tv/bl...

Sources

1. Society of Authors (2023)

Panel report on emerging technologies and creative practice.

2. University of Cambridge & Minderoo Centre for Technology and Democracy (2025)

Report on novelists and generative AI, including concerns about replacement and unauthorised training of models.

3. University of Edinburgh & Alan Turing Institute (2024)

Research on AI as “cognitive scaffolding” in writing and academic workflows.

4. “It was 80% me, 20% AI”: Seeking Authenticity in Co-Writing with Large Language Models (2024)

arXiv preprint analysing perceptions of co-authorship with AI.

5. Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society (2024)

Survey on AI use and disclosure in writing.

Edward Peppitt

Edward Peppitt