If AI Helps You Write… Who Owns the Words? A Writer’s Guide to Authorship in the Age of AI

AI can support planning, editing, and research but who owns the writing it helps create? A thoughtful look at authorship, ethics, and creative control

As AI tools become more widespread, many writers face a question they rarely voice: If AI helps you write, who owns the final words?

It’s a question that matters deeply because writing is not simply the production of sentences. It is an act of thought and intention. Authors guard their ideas. They protect their voice. With AI able to suggest outlines, reshape paragraphs, or even generate extensive passages, the sense of what it means to be “the author” becomes less certain.

Some argue the answer is obvious. AI doesn’t own anything — legally or creatively — so the writer remains the author. Yet this response avoids a far more complicated truth: authorship is not just a legal category but a moral and creative one. The real issue is not copyright. It is control. And control is a continuum, not an on/off switch.

When AI Helps — and When It Takes Over

Consider three situations that many writers now encounter:

1. AI suggests an outline

You reshape it, change the flow, add your own ideas, and discard elements that don’t fit. You refine the structure until it expresses your meaning. Here, AI is a brainstorming tool — nothing more. Authorship remains entirely yours.

2. AI tightens a paragraph

You’ve produced the original thought. AI helps with clarity. You then refine the result to restore your tone. Again, the writing is yours. The tool becomes a grammar-and-style partner.

3. AI drafts whole pages

You give a prompt. The tool produces paragraphs. You lightly edit. You publish. In this scenario, the tool is generating meaning and language at scale. Your creative input is greatly reduced. Your editorial decisions are shallow. In this case, authorship becomes ambiguous.

The distinction between these situations is control. If you shape meaning, voice, structure, and argument, then you remain the author. If the tool generates those elements, then authorship becomes diluted.

Why This Matters to UK Writers Today

A 2025 study by the Minderoo Centre for Technology and Democracy and the University of Cambridge found that more than half of UK novelists believe AI will eventually replace their work, and many feel their writing has already been used, without permission, to train commercial AI systems.

One novelist quoted in the report expressed the emotional impact simply:

“This is my life’s work. I can’t bear the thought of it being scraped and remixed into something I didn’t choose.”

Similarly, a publisher interviewed for the research warned:

“Our creative industries are not expendable collateral damage in the race to develop AI. They are national treasures worth defending.”

These concerns aren’t theoretical. They reflect a real fear that authorship itself — the idea of a crafted, human-made work — could erode if AI becomes too deeply embedded in the writing process.

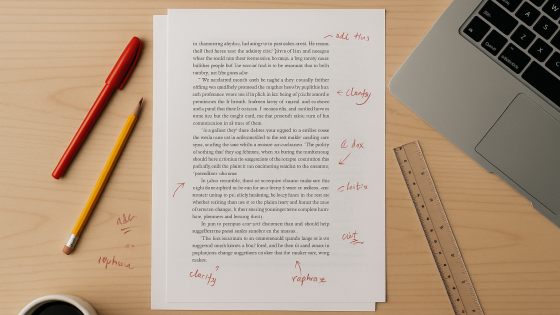

AI Can Strengthen Writing — If You Stay the Author

Despite these anxieties, many writers are finding that AI can strengthen their craft when used deliberately. A 2024 study, “It was 80% me, 20% AI: Seeking Authenticity in Co-Writing with Large Language Models,” showed that writers who used AI as a supportive tool still felt in control of their voice. Readers too often could not distinguish between AI-assisted and traditional human writing when the writer maintained full authorship of ideas, tone, and structure.

The key is intentionality. AI can:

- Suggest alternative phrasings

- Test different structures

- Clarify complex arguments

- Highlight unclear logic

- Reduce overwhelm in early planning

- Speed up research checks

But these are support functions, not replacements for creativity. AI can help you think better, but it cannot think on your behalf. It can refine meaning, but it cannot originate meaning.

You remain the author only if you remain the thinker.

The Moral Core of Authorship: Being Honest with Yourself

The real ethical question is not whether AI is “allowed” but whether you can honestly claim the writing as your own.

If you rely on AI to polish your sentences or test structures, you remain the guiding force. If you rely on AI to generate large volumes of prose, you drift into being a curator rather than a creator.

As novelist Zadie Smith wrote:

“A writer’s duty is to find the truth inside themselves — not to settle for borrowed phrases.”

When AI becomes the source of your phrasing, rather than a tool to refine your own, something essential shifts.

Why Ownership Still Belongs to the Human Writer — If You Stay in Control

Authorship rests on intention and agency.

If the ideas originate with you, the structure reflects your thinking, and the emotional charge of the writing is shaped by your judgement, the work is yours — regardless of whether AI offered a cleaner sentence along the way.

AI becomes ethically problematic only when it reduces your thinking. When it replaces struggle with shortcuts. Discovery with convenience. Or originality with imitation.

You are the author if:

- You originate the ideas

- You shape the argument

- You make the meaning

- You refine the tone

- You check the facts

- You direct the tool, not the other way around

Authorship is not threatened by the presence of AI. It is threatened by the absence of intentionality.

The Truth About AI and Your Writing — Workshop Page

If you’d like a clear, practical introduction to using AI responsibly in your writing, join my live three-hour workshop on Thursday 15th January for just £47 + VAT.

https://www.getpublished.tv/co...

Self-Publish Properly - Live - Workshop Page

For writers preparing to self-publish, check out my 5-day complete guide to writing, editing, and launching your book.

https://www.getpublished.tv/co...

More From the Blog

For more articles for writers who want clarity, confidence, and practical guidance, visit my blog.

https://www.getpublished.tv/bl...

Sources:

1. Minderoo Centre for Technology and Democracy & University of Cambridge (2025)

Generative Artificial Intelligence and UK Novelists

https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/...

2. The Guardian (2025)

“More than half of UK novelists believe AI will replace their work”

https://www.theguardian.com/bo...

3. “It was 80% me, 20% AI”: Seeking Authenticity in Co-Writing with Large Language Models (2024)

https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.130...

4. Zadie Smith — views on authenticity in writing

Themes discussed in Changing My Mind: Occasional Essays (Hamish Hamilton, 2009) and in various public talks on originality and voice.

Categories: : Support for Authors

Edward Peppitt

Edward Peppitt